The slides for tomorrow’s presentation of my paper with Frequent Commenter Scott are now available online—not that they will make much sense without my allegedly-engaging patter attached.

Thursday, 7 January 2010

Sunday, 26 July 2009

Rule of thumb: 10% of the public will believe anything

Greg Weeks is somewhat surprised by some of the numbers that Gallup found in a survey of Latin Americans in 2008 regarding the likelihood of their country experiencing a military coup:

Honduras had the second highest percentage of people (29%) who agreed that the country was moving toward a coup (behind Bolivia at 36%).

Those countries are not surprising. But 11% of Chileans? And 14% of Colombians? And then 11% in Costa Rica, where the military was abolished before most of its citizens were even born?

I’m not particularly surprised by these numbers. Not so much because the region is inherently unstable, or even because media coverage of events elsewhere perhaps has had a fear-inducing effect, much as the media hysteria surrounding the disappearances of random white teenage girls or the omnipresence of Chris Hansen has fed public fears well out of proportion to the actual threats to children and young adults.

Instead, because an appreciable percentage of the public falls into one of the following categories: having difficulty understanding the questions being posed; really, really wanting the interviewer to shut up and leave them alone; or genuinely holding rather crazy beliefs. To identify one example, approximately 6% of Americans believe the Apollo moon landings were staged, an idea far more preposterous (to my mind at least) than the idea that Colombia might experience a coup in the not-so-distant future.

It’s also possible there were some contextual effects in the survey that aren’t clear from Gallup’s description of it. It seems likely the question was posed in the same survey reported here on self-perceptions as “socialist” or “capitalist,” which may have had the effect of priming the responses of the interviewees—to say nothing of whether or not the typical democratic citizen understands the labels “capitalist” or “socialist” in any meaningful way. By emphasizing this area of conflict the survey may have led respondents to believe left-right conflict in their nations is more salient than it really was, and thus that military intervention might happen.

And, finally, while Costa Rica lacks formal armed forces, the country’s Fuerza Pública and separate special forces detachment sound a lot like military forces to me—and certainly could function sufficiently like one to toss Oscar Arias on a plane headed elsewhere if they were so inclined.

So to my mind it really isn’t overly surprising that a sizable percentage of average Chileans, Costa Ricans, and Colombians—particularly those who are disengaged from politics—would reportedly be willing to agree with the proposition their country is headed towards a coup.

(Updated to clarify that Costa Rica’s Fuerza Pública and special forces are separate from each other.)

Wednesday, 11 March 2009

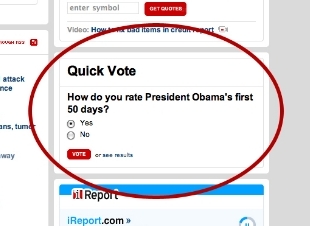

Quickie Poll Fail

I would like to thank CNN for giving me the ultimate example of the Worst Web Poll Ever for my semi-annual classroom rant about self-selected Internet surveys:

Huzzah and kudos to Burt Monroe (via Facebook) for the link. If the EPOVB section of APSA ever makes a T-shirt, this should be the picture on it.

Tuesday, 10 March 2009

Rushing to Judgment

Cassandra at Villainous Company points at some real data that indicate that a large chunk of Americans really, really dislike Rush Limbaugh. While perhaps this is the result of false consciousness or just uninformed judgment, my gut feeling is that it stems from Rush being a self-important, loud-mouthed blowhard who gets far too much credit among the party his continued existence on the face of this earth (or at least in the media) is increasingly a liability for due to his marginal role in rallying Republican support in the 1994 midterms that led to the GOP takeover of Congress.

Thursday, 18 December 2008

Another day, another syllabus

My current draft of my graduate political behavior seminar syllabus. There are a few holes here and there—and I know it’s probably closer to a senior seminar-level syllabus at a more selective institution—but I’m confident I can refine it a bit in the next few weeks while I tackle the easier syllabi.

Wednesday, 3 December 2008

Shoehorning

Public opinion, voting behavior, parties, and interest groups all shoved together in one unholy syllabus. And the best part is that I couldn’t even figure out how to cram in two books I’ve already ordered, which no doubt will annoy the bookstore to no end.

Wednesday, 29 October 2008

Your new life as a guinea pig

In the last 24 hours, I’ve been asked to disseminate two survey links. So have at them:

A research team from the Psychology Department at New York University, headed by Professor Yaacov Trope and supported by the National Science Foundation, is investigating the cognitive causes of voting behavior, political preferences, and candidate evaluations throughout the course of the 2008 U.S. Presidential election. This stage of the study focuses on the information people use to inform evaluations during the last few weeks before the election. They seek respondents of all political leanings from all over the country (and from the rest of the world) to complete a 15-minute questionnaire, the responses to which will be completely anonymous. The survey is here.

I also have a briefish survey from some students of a friend of mine at Auburn University, for those with less time to spare.

Standard disclaimers regarding the fact I know this is a convenience sample apply; complain at the principal investigators if you must.

Wednesday, 22 October 2008

QotD, Tversky found exceptions to the rule edition

A commenter at Kids Prefer Cheese demonstrates the application of heuristics to Internet dialogue:

You know how people use cognitive short-cuts to make sense of the world? For example, I could go read Ransom’s entire blog, probably do a bunch of background reading on Austrian business cycles, and then figure out whether he’s right about Cowen. Or I could use a simplifying heuristic which goes like this: people who post in all caps in blog comments are usually wingnuts. Sorry, Ransom, maybe you’re right, but in my book you’ve already lost on style points.

Monday, 15 September 2008

Hilzoy: Not a public opinion scholar

Hilzoy wonders why more people think Barack Obama will raise their taxes than think John McCain will, despite fancy graphs indicating that neither will raise most peoples’ taxes. Three broad hypotheses spring to mind:

- Voters do not believe Democrats (and Obama in particular) are credible on promising tax cuts or holding the line on taxes. Obama’s vote for a budget resolution that contemplated raising taxes (even if, in of itself, it did not raise them) does not help his credibility on this score. The inscrutability of how Washington works to the average voter strikes again—a similar procedural-versus-substantive vote issue, after all, was the basis for John Kerry’s “for it before he was against it” problem.

- Voters do not believe that the promises on the campaign trail regarding taxes reflect the situation that both candidates will face after the election. Presidents do not decide fiscal policy in a vacuum; instead, both will face a left-of-center Congress committed to both the appearance of fiscal responsibility and more progressive tax rates. For example, a “solidarity” tax increase on a greater portion of the “middle class” than anticipated by Obama (however “middle class” is defined) to fund programs like universal health care is not unlikely.

- It’s all heuristics. Voters have no actual knowledge of either candidates’ tax plans (rationally or irrationally—I’d argue rationally, due in part to point 2) and are relying on a schematic conception of politics in which Democrats are seen as more likely to raise taxes than Republicans.

Notice in the full report of the poll results the graph labeled “Economic Groups Perceived to Benefit Most in an Obama or McCain Presidency,” in which the heuristic perceptions of the public comport to a greater degree to the promised tax plans, in large part because both candidates are promising plans that—in their effects on various subsets of the population—are more consistent with what we’d expect Republican and Democratic fiscal policies to emphasize.

Incidentally, none of these explanations require voters to even be aware of the campaign spin regarding Obama’s tax positions; one suspects most voters aren’t.

Saturday, 26 January 2008

Old wine in new bottles

Josh Patashnik of The New Republic discovers that Republicans and Democrats have divergent beliefs about the state of the national economy (þ: JustOneMinute). Clearly he doesn’t have a subscription to the American Journal of Political Science, where my dissertation chair and two co-authors showed this to be the case seven years ago based on 1990s data, well before George W. Bush set up camp in the Oval Office (see also Duch and Palmer 2001, which demonstrates the same effect among Hungarian voters).

The moral of the story: those who do not read the political science literature are condemned to reinvent it.

Friday, 25 January 2008

Math works

I had fun today in class with the following formula: 0.98/√N.

Wednesday, 3 October 2007

Carbonized opinion

My seemingly-biweekly contribution to OTB this time is about the simultaneous popularity of doing something about climate change and unpopularity of using carbon taxes to do it.

Tuesday, 11 July 2006

Survey questions are intrusive measures

Tyler Cowen has the evidence.

Tuesday, 6 December 2005

What a gas

The president’s poll numbers appear to be recovering as of late, and there are two major competing theories to explain the change. Charles Franklin appears to attribute the change to the new PR pushback from the White House, which we might term the Feaver-Gelpi thesis (see also Sunday’s NYT), while Glenn Reynolds says it’s the gas prices and the Mystery Pollster suggests good economic news in general.

It may be the most simplistic thesis, but I think the “pump price” explanation is probably the most plausible; unlike other information, gasoline prices are unavoidable information for most voters and not subject to partisan spin, unlike the presidential pushback on Iraq and news of the general economic recovery—both of which can be spun negatively in a way that falling gasoline prices really can’t. In a noise-filled informational environment, I suspect clear “pocketbook” signals like gasoline prices are much stronger cues for presidential support than the world of competing, ideologically-based claims over Iraq and interest rates.

Update: Al Qaeda appears to put some stock in the pump price explanation as well.

Friday, 28 October 2005

Fun with data mining

I’ve been doing some SPSS labs with my methods class this semester, and I stumbled upon a mildly interesting little finding: in the 2000 National Election Study, the mean feeling thermometer rating* of gays and lesbians is higher among respondents with cable or satellite TV than among those who do not have cable/satellite. It’s marginally significant (p = .057 or so in a two-tailed independent-samples t test). I’m not sure if the cable/satellite variable is standing in for a “boonies versus suburbs/urban areas” thing or something else.

It’s also fun because the test is significant at the .05 level if you do a one-tailed test (though, since I have no a priori theory as to why cable/satellite households would like gay people more than non-cable households, I’m not sure a one-tailed test is legitimate), but not significant at .05 if you do a two-tailed test, so it’s useful in illustrating that marginal case.

Thursday, 27 October 2005

Social desirability in action

Colby Cosh points out a poll showing that nearly 40% of Canadians would never vote for a candidate for public office with a history of alcoholism. Is it the prudes or the pollsters? Colby suspects the latter, and I am inclined to agree.

Tuesday, 2 August 2005

Content analysis of The Daily Show

Paul Brewer presents the results of a content analysis of The Daily Show conducted by some of his students and himself; the statistics lend credence to suggestions that TDS presents a lot of political information to its viewers.

Mind you, whether this is an appropriate substitute for making citizens sit through The NewsHour is an open question, one best left to people with a far more normative bent than my own.

Thursday, 30 June 2005

Why political scientists try to be irrelevant

Today’s Washington Post carries a front-page article that (inadvertently) explains why empirically-oriented political scientists* like myself for the most part avoid doing anything that has anything close to real-world implications. And, it’s a no-win situation unless you’re a raging lefty “new politics” type (i.e., the sort who wouldn’t be hired by Democrats or Republicans to do this sort of work in the first place): somehow I doubt those in our discipline who want our discipline to be more “relevant” will be cheering the efforts of my future colleagues Peter Feaver and Christopher Gelpi to reinforce public support for the Iraq war and the War on Terror.

James Joyner’s comments further underscore the reasons for this reluctance:

Peter Baker and Dan Balz have a front page editorial, er “analysis,” at the Washington Post pointing out that President Bush is a politician who crafts his public speeches with his audience in mind. Even more damning is the suggestion that he hires experts to advise him.

Another data point: a few weeks ago, I made the mistake of trying to explain 50 years of empirical public opinion research to a reporter for the Jackson Free Press (for this article) who was asking why nobody voted in Jackson’s mayoral race, and all I got for it was being accused of being a “cynic.” Talk about shooting the messenger.

![Welcome to Signifying Nothing [Signifying Nothing]](/local/memlogo-1.png)